Design Thinking: Shine On, You Double Diamond

- Sarah

- Nov 14

- 7 min read

When I started the International Programme in IT and Learning at GU, I brought with me a background in graphic design, and several years of designing processes and systems in higher education with a design thinking mindset. For me, "design thinking" comes naturally, so it was mind-blowing to read and steep so much in the concept in what we call "the design course" over in Applied IT on the Lindholmen campus.

Have you ever caught yourself thinking, “There has got to be a better way to do this?” That small spark of curiosity is where design thinking begins. Rearranging desks to foster collaboration, imagining a smarter ride-sharing system, enlarging text in a presentatiaon so everyone can read, reframing a question mid-interview, or inventing a fix for a cluttered drawer… these are examples of design thinking. Moments of noticing, questioning, and experimenting combined with instincts to observe, empathize, and improve the world around us are at the core of the concept of design thinking. It starts with people-watching.

“Requirements produced by asking people what they need are invariably wrong. Requirements are developed by watching people in their natural environment.”

Donald Norman, 2013,

The Design of Everyday Things

“Design thinking” is a term born from the study of design beyond the visual, and this approach has become an underpinning of innovation in technology, learning, and virtually every thoughtfully considered human activity. As Löwgren and Stolterman remind us, design is never neutral. Sketches, prototypes, and interfaces we create shape the ways people live, learn, and make sense of their world. Even unintended choices, the “side effects or consequences of mistakes or lack of knowledge” become part of people’s lived experience.

“[T]o design digital artifacts is to design people’s lives.”

Jonas Löwgren & Erik Stolterman, 2004, Thoughtful Interaction Design: A Design Perspective on Information Technology

An Expansive Approach to Solving Problems

Design thinking is a way of approaching complex problems by focusing on human needs and iterating toward better solutions. In design, there are no rules, but there are always people involved. The best designers invite others to the table. A variety of stakeholders are considered and engaged while the designer(s) decide(s) which methods and skills to borrow or develop. Don Norman (2013) described design as an iterative and expansive process in which designers resist the urge to jump to conclusions:

“They first spend time determining what basic, fundamental (root) issue needs to be addressed… They don’t try to search for a solution until they have determined the real problem… Only then will they finally converge upon their proposal.”

Donald Norman, 2013,

The Design of Everyday Things

Designing the Design Process

Design is not only about the artifact, but about how the design process itself is constructed. It requires people skills as much as any technical or artistic know-how.

“Great design requires… great management… the hardest part of producing a product is coordinating all the many, separate disciplines, each with different goals and priorities.” (Norman)

Löwgren and Stolterman write,

“The thoughtful position is to view the whole situation as a design task: to design the design process.”

Basically, designers continually shape their own methods, choosing which perspectives to include, which voices to prioritize, who to work with, and which tools to use. The d.school at Stanford echoes this. “There is no ONE way of teaching design… what matters most are the higher-order design abilities—creative competencies that allow people to navigate ambiguity and complexity.” (d.school, 2022) This flexibility makes design thinking a valuable framework for learners and educators alike: it fosters agency, reflection, and adaptability - skills essential in today’s technology-mediated work and living landscape.

The Double Diamond and Other Conceptions of Design

The Double Diamond model, developed by the UK Design Council, is recognized globally as one essential framework of the design thinker’s process in two phases: divergence and convergence. User Experience (UX) and Interaction Designers are likely familiar with this nearly universal model. The first diamond explores the problem space - through research, observation, and empathy - before narrowing to define the real challenge at what I like to call “the pinch point.” The second diamond widens again in ideation, then narrows to converge on prototyping and delivering solutions. There are an infinite number of interpretations of this model, mostly highlighting that design is not linear but involves phases of focusing, opening, adapting, adding, subtracting, and adjusting to create human-centered, functional artifacts, processes, and tools.

The Double Diamond (4 Ds: Discover, Define, Develop, Deliver) model of design thinking (© Fluxspace, 2023; available at https://www.fluxspace.io/resources/the-4-ds-double-diamond-design-thinking-model

The Stanford d.school, one of the leading institutions in design education, initially framed design thinking as a series of interconnected modes: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test (d.school Starter Kit). However, the d.school is the first to admit that these steps can be misconstrued as a “design process.” Yet again, this model shows designers’ thinking is not linear but can be considered linked phases that inform the next; each stage invites reflection, reframing, and iteration. The d.school says, “… everyone has the capacity to be creative”, and design thinking offers mindsets to unlock that creativity (d.school 8 Core Abilities).

The five‑hexagon framework from Stanford d.school illustrating design‑process modes (© Stanford d.school, 2016; available at https://dschool.stanford.edu/stories/lets-stop-talking-about-the-design-process

The Interaction Design Foundation (IDF) similarly defines design thinking as a human-centered approach to innovation, integrating empathy, ideation, and experimentation (Interaction Design Foundation, 2024). Value lies not only in solving problems, but in re-defining them: seeing beyond the obvious. The IDF poses a perspective for the end goal of design thinking via three lenses to uncover deeper, feasible user needs.

The Three Lenses of Design Thinking: desirability, feasibility, and viability (© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY‑SA 4.0). Source: Interaction Design Foundation

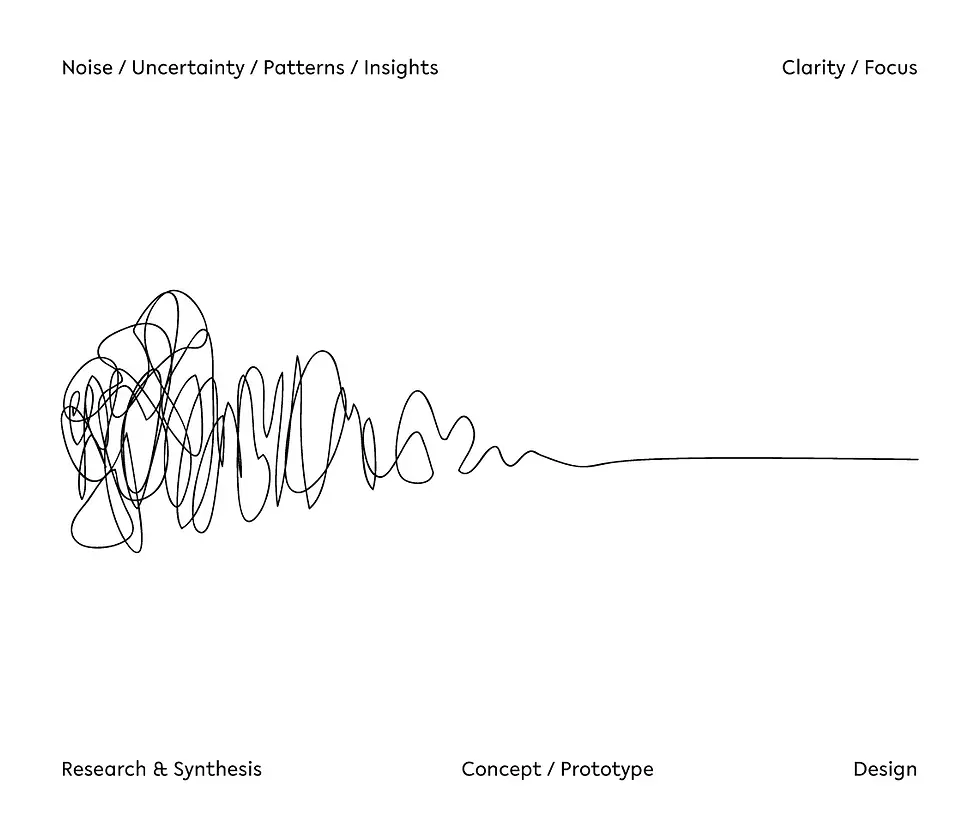

Newman’s Design Squiggle - the swirling, seemingly chaotic drawing by Damien Newman - captures the essence of creative work with a dash of humor. It begins in a tangle of loops on the left, representing uncertainty, exploration, and divergent thinking… then moves toward a straight line of clarity and focus as ideas coalesce and converge. The squiggle, like innovation, isn’t tidy or linear. Design is messy, iterative, full of loops and backtracks, and the real path to insight often comes only after sitting in and embracing a complex mess of ideas and moments.

The Design Squiggle, illustrating the messy early phase of creative work through to clarity (© Damien Newman; available at https://medium.com/how-this-works-co/damien-newmans-squiggle-as-a-critical-look-at-design-thinking-0ca8ffaab802

Design Thinking as Divergence and Discovery

Good designers, Norman writes, “never start by trying to solve the problem given to them: they start by trying to understand what the real issues are.” This is what makes design thinking so powerful in learning and research contexts… it promotes divergence before convergence, encouraging exploration of multiple perspectives rather than settling too early on a single answer.

Löwgren and Stolterman (2004) add that design involves “an ongoing conversation between the designer and the situation." Sketches, models, and drafts serve as external representations of that conversation: they make ideas visible and tangible. At Stanford’s d.school, this mindset is called a “bias toward action," the belief that creativity emerges through doing, testing, and learning (d.school Bootleg).

You have probably heard several catch-phrases embodying this school of thought: fail early, fail often… move fast, break stuff… these quips could well be finished and refined by adding that after several iterations, you have to pluck the successful pieces out and put them together for the best conceivable solution, then test, re-test, refine, and test again. This is the essence of design thinking.

Five Use Cases for Design Thinking

1. Education: Schools and universities use design thinking to help students tackle authentic, interdisciplinary challenges. Stanford’s K12 Lab has shown how empathy mapping and rapid prototyping can foster collaboration and creativity in classrooms.

2. Learning Experience Design (LXD): Instructional designers apply design thinking to craft learner-centered digital experiences; combining analytics, UX research, and iterative testing to refine dashboards, simulations, and online courses.

3. Accessibility: Organizations integrate design thinking to co-create tools with users who have disabilities, ensuring inclusive and equitable solutions through participatory design. Public entities like transportation systems, hospitals, and schools as well as private businesses and corporations employ design thinking to serve clientele in the most appropriate and ways, assuring they are also cost-effective.

4. Research: Qualitative researchers increasingly employ design thinking; co-developing research questions, storyboards, or prototypes with participants to surface insights.

5. Sustainability and Social Innovation: From community design labs to civic-tech initiatives, design thinking supports systems-level problem solving, enabling communities to envision futures that are both equitable and sustainable.

Why Design Thinking Matters

“Design is one of the more active processes in this attempt to make the world a better place.”

Jonas Löwgren & Erik Stolterman, 2004,

Thoughtful Interaction Design: A Design Perspective on Information Technology

As Löwgren and Stolterman remind us, “Every design process is a combination of actions, choices, and decisions that affects people’s lives and possible choices for action.” When we design, we are shaping possibilities—what can be seen, understood, or done.

Design thinking, when practiced thoughtfully, expands these possibilities. It helps us move from “how things are” toward “how things could be." Applying design thinking to research, taking this mindset into aims and questions, prototypes and tests, surveys and interviews, analysis and visuals, then into writing and revisions is the natural progression... you can see where I am going here. Just as the best designers are researchers, the best researchers are "design thinkers."

References

Fluxspace. (2023). The 4 Ds Double Diamond Design Thinking Model. https://www.fluxspace.io/resources/the-4-ds-double-diamond-design-thinking-model

Harvard Business School Online. (2023). What Is Design Thinking? https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/what-is-design-thinking

Interaction Design Foundation. (2024). Design Thinking. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/design-thinking

Löwgren, J., & Stolterman, E. (2004). Thoughtful Interaction Design: A Design Perspective on Information Technology. MIT Press.

Norman, D. A. (2013). The Design of Everyday Things (Rev. ed.). Basic Books.

Stanford d.school. (2022). Let’s Stop Talking About THE Design Process. https://dschool.stanford.edu/stories/lets-stop-talking-about-the-design-process

Stanford d.school. (n.d.). Design Thinking Bootleg & Starter Kit. https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/design-thinking-bootleg

Stanford d.school. (n.d.). 8 Core Abilities. https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/8-core-abilities

Newman, D. (2023). The Design Squiggle. https://medium.com/how-this-works-co/damien-newmans-squiggle-as-a-critical-look-at-design-thinking-0ca8ffaab802

Comments